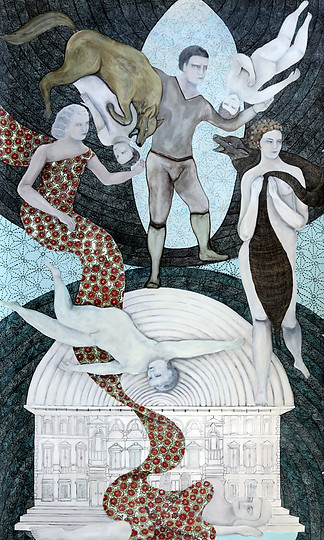

Triumph and Ecstasy

SOTIRÍA: Some thoughts on ‘Triumph and Ecstasy’

by CHRISTOS TSIOLKAS

Triumph and Ecstasy – new paintings by Robin Astley exhibited at Gallerysmith, Melbourne, Sept 13 - Oct 5, 2013.

Is salvation one of those words that is becoming obsolete; a word so embedded in two thousand years of monotheistic aspiration to transcend death and to transcend suffering, that it can no longer have any relevance in our secular, technological age? And if a word such as salvation does disappear, does that mean that an art of representing it is also to vanish, to belong only to the shadows of nostalgia and the past? Do we not need salvation anymore? Triumph and Ecstasy† reminds us that salvation has a longer history than the God of Abraham. There are the myths of the heroes: the stranger who answers a people’s prayers or sacrifices, who arrives to liberate them from tyranny; the hero who slays the monster. There are the totemic gods before the Word, the gods who died and were reborn in order to save us from the chaos and amoral cruelty of nature. And Robin Astley’s work – the scale of the paintings, the monumental depiction of the figures within them – also remind us that even as atheists, as nonbelievers, we all experience those moments when our heart is broken, or our spirit or our body, and we call out in the darkness and towards the light, Please ¨someone anyone something' . Please save me. We have not conquered salvation. It is one of the most acute pleasures I receive from Astley’s paintings: the recognition that religious art, an art of meditation and exaltation, need not remain in those shadows, that it can still be a form of art that speaks to us and moves us. Her work borrows from across the history of religious and spiritual iconography, from prehistory to the Renaissance to the Ages of Reason and Unreason.

We are no longer the people of one god or of local gods. Triumph and Ecstasy recognises this irony but thankfully the work itself is not detached or ironic. Astley’s canvases respect and honour the truth and power of the Icon.

In other words, her work whispers to us: I understand, sometimes we need to lift our eyes to the skies and pray, Please ¨someone anyone something'. Please save us.

So salvation is a victory, a submission that results in transcendence. But Astley’s work warns us that salvation is not always triumphant. The hero is often attacked and sacrificed by the people he saved; the brother is killed by his twin, his blood blessing the city they raised together; and a young girl who hears God and raises an army to rout the invaders of her homeland, that girl is abandoned by God and expires in flames. Heroes and Saviours and Gods are there in Robin Astley’s canvases but I am drawn again and again to the three women in silent mourning. I am drawn to the figure of the donkey. Two women support a grieving mother at the tomb of her crucified son. How can she endure such misery? How can she muster the strength to trust in salvation? Patience. I think that the donkey – that beast who works and struggles and is burdened by the load it must carry – I think this donkey speaks to the terrible truth of salvation’s promise. It doesn’t fall from the sky, it is has to be fought for and earned. It comes with a price. And it is a lesson we have lost in the rush and the speed of our age. It is what I love about Robin Astley’s art, how it sings to us: Be still, be patient.

Text courtesy of Christos Tsiolkas Copyright 2013